The best myths surprise us.

It’s easy to forget this, now that over-simmered reductions of Joseph Campbell’s work have been aerosolized in our storytelling atmosphere. You know what I mean—that Cliffs’ Notes circle chart where the Hero Leaves Town at noon, enters the underworld at three, finds the grail at six, leaves the underworld at nine, and is exploded by Ozymandias’s Enormous Psychic Squid Monster at five minutes to midnight. (Or something.)

Spend too long staring at the circle and you forget it’s an analytical tool designed to identify structural parallels between complicated, twisty, weird tales—that Campbell’s approach is useful not because myths are all the same. Quite the opposite: myth’s a garden where strange fruit grows.

Here are a few of my favorites, stories that neatly sidestepped my expectations when I first heard them, and have wormed around under my skin since. Some of the surprise comes from different expectations I’ve developed growing up in transmilennial US-America rather than (say) the 10th century South Pacific, or the 1st century Middle East—which is awesome.

Advance warning, since I’ll be working with live traditions here: when I say ‘myth,’ I mean it in the descriptive sense (‘stories about gods, demigods, and supernatural events,’) not in the judgmental sense (‘stuff that never happened or is obvious bunk.’) Got it?

Good. Let’s go.

Nanahuatl and Tecuciztecatl

Nanahuatl and Tecuciztecatl

The gods tried to make humanity four times; the first four times it didn’t work out. They got it right on the fifth try—but they still needed to start the sun and moon moving in the sky after the last apocalypse. Of course, no god wanted to sacrifice him- or her-self to kickstart the sun, so they gods chose Tecuciztecatl, strongest and most handsome, to be the sun-sacrifice, and Nanahuatl, whose name literally means “Covered in Boils,” to die for the moon.

Tecuciztecal and Nanahuatl prepare themselves for death. But, when the day comes, Tecuciztecatl gets right up to the edge of the fire and, well—he chickens out. He can’t do it. So Nanahuatl jumps in and saves the world. Tecuciztecatl follows him, shamed, and becomes the moon.

Some mythologies praise their sun-god for his beauty, and my head’s full of beauty-and-strength-are-great myths. I love that here, the Baldur type flinches first, leaving the guy covered in sores to get shit done.

Loki’s Rap Battle

So, Loki, right? Trickster god, occasional Big Bad Evil Guy of Norse mythology. As of now (goes Norse cosmology), Loki’s trapped under the earth, bound in the entrails of his son, with snakes dripping poison into his eyes. When he writhes, the Earth shakes. (c.f. Sandman: Season of Mists.)

So why does Loki deserve such a punishment? Maybe the gods imprisoned him because he murdered Baldur the Brilliant? (Again with the glistening pretty-boys.) Or because he fathered Fenrir the Wolf who Eats the Moon? Or Jormungand World-Snake, who will slay Thor and be slain by him during Ragnarok?

Try “He won a rap battle.” More precisely, to appease any exacting and angry skalds who may be reading: he won an insult contest.

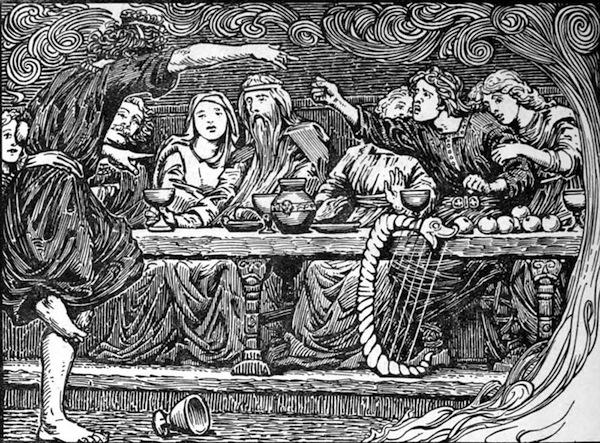

I can give no description that will match the actual text of the Lokisenna. If you want a more modern version, check out Myths Retold. Basically: nobody invites Loki to dinner, so he shows up and starts insulting everyone, baring their darkest secrets in public. So they chase him down and bind him beneath the Earth.

Karin Tidbeck introduced me to the Lokisenna; I knew the story, but didn’t know that this out of everything caused the binding of Loki. I don’t know about you, but I tend to think of the old Norse gods as being heavier on the ‘deeds’ end of the scale than ‘words.’ Yet it’s Loki’s insults that push Thor & company one step too far.

Buddha and the Monkey King

Buddha and the Monkey King

In the early chapters of the Chinese picaresque martial arts epic Journey to the West, a powerful immortal wizard martial arts master who’s also a stone monkey (it’s complicated) named Sun Wu’kong builds an army of fellow animal spirits and declares independence from the Jade Emperor of Heaven. A number of divine attempts to coerce and convert Our Hero follow, which culminate when Sun gets drunk on the peaches of immortality, beats up Laozi, (god I love Journey to the West) gets trapped in an alchemical crucible from which he emerges MORE POWERFUL THAN BEFORE!!!, and at last fights his way to the feet of the Jade Emperor himself, ready to knock the king of heaven off his throne.

At which point the Buddha shows up and, after demonstrating his basic omnipotence, imprisons Sun under a giant mountain. So far, so Paradise Lost—in general outline at least, and told from a ‘Satanic’ viewpoint (though Sun Wukong is a lot funnier, more sympathetic, and, though of course your mileage may vary, more interesting than Satan). Cue hubris, sin, eternal damnation, etc. Right?

Actually, cue a work-release program after a brief five centuries of incarceration: Sun Wukong’s let out to protect a pilgrim making a religious journey. In the process, he learns compassion, patience, and Buddhism—becoming a better person, but not, critically, a different person. As the story progresses, he remains as funny, brilliant, active, and brave as he was in its first chapters, though he learns more about only with greater understanding of his place in the cosmos. As rebellions against Heaven go, this is a surprisingly good outcome.

Mark 11:12-25, a.k.a. “God Hates Figs”

Just before the Passion of St. Mark—neatly bracketing the scenes in which Jesus kicks moneylenders out of the Temple—Jesus encounters a fig tree not bearing fruit, and curses it. Later, after the scene with the moneylenders, Jesus and the apostles ride past the same fig tree and find it withered.

Huh? Did God really just smite a fig tree?

Exegesis on this passage abounds, precisely because of that moment of surprise. Chasing moneylenders out of the temple with a bullwhip seems like something a messiah might do. But cursing a tree that just doesn’t happen to have fruit when you need it? (And yes, figs were out of season around Passover, but apparently pre-fig buds called taqsh grow before figs ripen, and those are edible, and like many questions of biblical interpretation this is a rabbit hole which holds the Scenes from a Multiverse rabbits—I’ll back out slowly now.) Jesus himself, when asked for an explanation, preaches about the power of prayer—but that doesn’t answer the why.

I’m a storyteller, not a theologian. For me, it’s hard to read this scene out of the context of the Passion. “I’m a week from crucifixion, and I just wanted a snack. Dammit! …Ooops.” But whether you prefer that reading or a more traditional exegesis, this story sticks in the brain precisely because of how strange and surreal it seems in the Gospel context.

This is my favorite surprise in myth; it’s a story from the Cook Islands.

Tinirau was the god of the sea, living (at the time our story begins) as a mortal man, with a mortal wife. His son, Koro, did not know his father’s true nature—all he knew was that Tinirau would go away for nights at a time and return exhausted, smelling of sweat and drink and sea. So one night, he followed his father.

Koro saw Tinirau collect coconut meat in a pandanus leaf, walk down to the ocean, and sprinkle the coconut meat into the ocean while chanting a strange song. Suddenly the sea boiled with fish, summoned by Tinirau, and the Sacred Isle rose upon the horizon—a wandering magical land full of Tinirau’s subjects, fish-spirits who could seem human if they so chose. Tinirau walked out onto the water and danced and sang with the fish who’d come to see him. Koro was amazed—especially by the dancing, which he had never seen before. (This was before human beings knew how to dance.)

The sacred isle retreated over the horizon, bearing Tinirau, and the fish returned to their depths; a few days later, Tinirau came back to land.

The next time Tinirau went out, Koro followed him—and saw the same celebration, the same dancing, the same retreat. After Tinirau disappeared, Koro, who watched and remembered, performed the ritual and chanted the chant as his father had done.

And the fishes came, and the sacred island, and his father upon it.

What do you think happens next, Dear Reader? Does Koro burst into flame Semele-style? Transform to a pillar of salt, like Lot’s wife? Does a Bridge of Birds-esque tragic separation of human and divine ensue? Is he drowned, perhaps, or maybe something with a smattering of Cthulhu considering the fish-folks? Maybe the ocean’s destroyed, or almost destroyed, a la Phaeton?

Here’s how the story ends: Koro’s father smiles, extends his hand, and invites his son to join him. They sing together with the people of the sea, and dance under the stars. And when the revels end, Koro returns to shore, and teaches humankind to dance in turn.

There’s a place for pillars of salt, and piles of ash, and bridges of birds, and Cupid and Psyche. But every once in a mythic while, it’s a nice surprise to find a story where curiosity’s answered with love, and dancing.

Max Gladstone writes books about the cutthroat world of international necromancy: wizards in pinstriped suits and gods with shareholders’ committees. You can follow him on Twitter.